Subscribe To Get Latest Updates!

Decision Making

Have you ever stood in front of a menu, torn between your favorite dish and a tempting new option? Or perhaps you’ve faced a tough choice between two job offers, each with its own set of pros and cons. These everyday scenarios illustrate the essence of decision making – the process of choosing one path from a multitude of possibilities.

Decision making is something we all do, every single day. It’s the mental gymnastics we engage in when we weigh options and pick the best one, whether it’s as simple as deciding what to eat for breakfast or as complex as determining the direction of our career.

Imagine you’re planning a weekend getaway with friends. One friend suggests a beach trip for some sun and relaxation, while another proposes a hiking adventure in the mountains. Both options sound appealing, but you have to consider factors like weather, cost, travel time, and the preferences of everyone involved before making a decision.

In another scenario, imagine you’re a business owner trying to decide whether to invest in new technology for your company. On one hand, the technology could streamline operations and increase productivity. On the other hand, it’s a significant financial investment, and there’s no guarantee it will deliver the expected returns.

These examples highlight the complexity of decision making. It’s not just about choosing between right and wrong; it’s about navigating through uncertainty, weighing risks and rewards, and considering the impact of our choices on ourselves and others.

In this article, we will cover what decision making is all about, from understanding what influences our choices to practical methods for making better decisions in both personal and professional situations. So, let’s dive in and explore the fascinating world of decision making together!

Table of Contents

1. Introduction to Decision Making

Decision making is the process of selecting the best course of action among several alternatives to achieve a desired outcome or goal. It involves identifying a problem or opportunity, gathering relevant information, evaluating potential options, and choosing the most suitable option based on various criteria such as feasibility, effectiveness, efficiency, and potential risks.

Decision making occurs in various contexts, including personal, professional, organizational, and societal levels. It can range from simple, routine choices to complex, strategic decisions with significant consequences. Effective decision making often requires critical thinking, analysis, judgment, creativity, and sometimes collaboration with others.

There are different approaches to decision making, including rational decision making, which involves systematically weighing pros and cons to arrive at the best choice, and intuitive decision making, which relies on gut feelings and past experiences. Additionally, decision making can be influenced by cognitive biases, emotions, cultural factors, and external pressures.

Ultimately, the quality of decision making can greatly impact individual success, organizational performance, and societal progress. Therefore, developing effective decision-making skills is crucial for navigating various challenges and opportunities in life.

1.1 Definition of Decision Making

There are several standard definitions for decision making used in various fields such as psychology, management, economics, and sociology. Here are a few examples:

Psychology: “Decision making is the cognitive process resulting in the selection of a belief or a course of action among several alternative possibilities.” (Source: Wikipedia)

Management: “Decision making is the process of making choices by identifying a decision, gathering information, and assessing alternative resolutions.” (Source: BusinessDictionary)

Economic: “Decision making involves choosing between various courses of action or inaction.” (Source: Investopedia)

Sociological: “Decision making is the process by which individuals or groups choose courses of action from among multiple alternatives.” (Source: Sociology Guide)

Political Science: “Decision making refers to the process of choosing among competing alternatives to formulate and implement public policies.” (Source: American Political Science Association)

Computer Science: “Decision making is the process of selecting a logical choice among the available options based on predefined criteria.” (Source: Techopedia)

Neuroscience: “Decision making is the mental process of selecting a course of action from several alternatives. It involves assessing multiple options and making predictions about the outcome of each option.” (Source: National Institutes of Health)

These definitions offer insights into how decision making is conceptualized and studied across diverse academic and professional fields.

1.2 Importance of Decision Making

The importance of decision making lies in its pervasive influence on various aspects of life, ranging from personal well-being to organizational success and societal progress. Here are some key points highlighting its significance:

Problem-solving: Decision making is at the core of problem-solving. It enables individuals and organizations to identify challenges, analyze them, and devise effective solutions to address them.

Achieving goals: Effective decision making helps individuals and organizations set and achieve their goals. By making informed choices, they can align their actions with their objectives and move closer to desired outcomes.

Resource allocation: Decision making involves allocating resources such as time, money, and manpower. Wise allocation ensures optimal utilization of resources, leading to improved efficiency and productivity.

Risk management: Decision making involves assessing risks and uncertainties associated with different options. By making calculated choices, individuals and organizations can mitigate risks and minimize potential negative consequences.

Innovation and growth: Decision making often involves exploring new ideas and opportunities. Embracing innovative choices can drive growth, foster creativity, and lead to continuous improvement.

Conflict resolution: Decision making plays a crucial role in resolving conflicts and addressing disagreements. By making fair and well-considered decisions, individuals and organizations can foster harmony and cooperation.

Leadership and influence: Effective leaders are skilled decision makers who inspire trust and confidence. Their ability to make sound decisions, even in challenging circumstances, earns them respect and influence.

Adaptability: In a rapidly changing world, decision making enables individuals and organizations to adapt to new situations and seize emerging opportunities. It fosters flexibility and resilience in the face of uncertainty.

Ethical considerations: Decision making involves ethical considerations and moral principles. By making ethical choices, individuals and organizations uphold integrity, fairness, and social responsibility.

Learning and development: Decision making is a learning process. Through reflection on past decisions and their outcomes, individuals and organizations can gain valuable insights, refine their decision-making skills, and grow personally and professionally.

Overall, the importance of decision making cannot be overstated. It empowers individuals and organizations to navigate complexities, make choices that align with their values and objectives, and ultimately shape their present and future trajectories.

2. Decision Making Process

The decision-making process is a fundamental aspect of how individuals and groups navigate through choices and make selections. It’s a structured approach used to solve problems, seize opportunities, and address challenges. Imagine it as a roadmap guiding us from recognizing a need for action to implementing a chosen solution and learning from the experience. By breaking down decision-making into manageable steps, we can make more informed choices and achieve better outcomes. In this section, we’ll explore each stage of the decision-making process, unraveling its simplicity and significance in everyday life and business.

2.1 Identifying the Need for a Decision

Identifying the Need for a Decision is the foundational step in the decision-making process where individuals or organizations recognize that a decision must be made in response to a specific situation or challenge. This step involves several key aspects:

Problem Recognition: It begins with recognizing that there is a problem, opportunity, or challenge that requires attention. This could be triggered by various factors such as changes in the external environment, internal issues within the organization, or emerging trends in the market.

Sense of Urgency: The identification of the need for a decision often involves a sense of urgency or importance. Decision makers may perceive the situation as critical or time-sensitive, prompting them to take action promptly to address the issue at hand.

Clarity of Purpose: It’s essential to have a clear understanding of the purpose or objective of the decision. This involves articulating what needs to be achieved or resolved through the decision-making process, whether it’s solving a problem, capitalizing on an opportunity, or addressing a challenge.

Stakeholder Awareness: Decision makers should also consider the stakeholders who may be affected by or have a vested interest in the decision. Identifying key stakeholders and understanding their perspectives, concerns, and expectations can help ensure that their needs are taken into account during the decision-making process.

Trigger for Action: There may be specific triggers or indicators that prompt the need for a decision, such as unexpected events, changes in performance metrics, feedback from stakeholders, or the emergence of new opportunities or threats in the external environment.

Overall, the process of identifying the need for a decision involves being proactive and attentive to the signals and cues that indicate when action is required. It sets the stage for the subsequent steps in the decision-making process by clarifying the problem or opportunity at hand and creating a sense of purpose and direction for the decision-making efforts.

2.2 Defining the Decision Criteria

Defining the Decision Criteria is a critical step in the decision-making process where individuals or organizations establish the specific standards, goals, or objectives that the decision must fulfill. This step involves several key aspects:

Clarity of Objectives: It begins with clarifying the overarching goals or objectives that the decision is intended to achieve. This could include desired outcomes, performance targets, or strategic priorities that guide the decision-making process.

Identification of Criteria: Decision makers identify the specific criteria or factors that are relevant to evaluating alternative options. These criteria serve as the yardstick against which different alternatives will be measured and compared. Examples of decision criteria may include cost-effectiveness, feasibility, alignment with organizational values, risk level, stakeholder impact, and time constraints.

Prioritization of Criteria: Not all decision criteria are equally important or relevant to every decision. Therefore, it’s essential to prioritize the criteria based on their relative importance and relevance to the decision at hand. Decision makers may assign weights or ranks to each criterion to reflect its significance in the decision-making process.

Alignment with Goals: The decision criteria should align closely with the overarching goals or objectives of the decision. They should reflect the key considerations that will drive the selection of the best alternative to achieve the desired outcomes.

Specificity and Measurability: Decision criteria should be specific, measurable, and clearly defined to facilitate objective evaluation and comparison of alternative options. This may involve quantifying criteria wherever possible or using qualitative descriptors to ensure clarity and precision.

Inclusivity and Consensus: In collaborative decision-making settings, it’s important to involve relevant stakeholders in defining the decision criteria. Seeking input from diverse perspectives can help ensure that the criteria are comprehensive, balanced, and reflective of the interests and priorities of all stakeholders involved.

Overall, defining the decision criteria provides a structured framework for evaluating alternative options and making informed decisions that are aligned with organizational goals and values. It sets the stage for the subsequent steps in the decision-making process by establishing clear benchmarks for assessing and comparing alternative courses of action.

2.3 Gathering Information

Gathering Information is a crucial step in the decision-making process where individuals or organizations collect relevant data, facts, and insights related to the decision at hand. This step is essential for ensuring that decision makers have a comprehensive understanding of the problem, opportunity, or challenge they are facing, as well as the factors that may influence potential solutions. Here’s a closer look at the key aspects of gathering information:

Identification of Information Needs: The process begins with identifying the specific information that is needed to inform the decision-making process. This may include data on market trends, customer preferences, competitor actions, technological advancements, regulatory requirements, financial implications, and other relevant factors.

Sources of Information: Decision makers gather information from a variety of sources, including internal and external sources. Internal sources may include organizational databases, reports, performance metrics, and expertise from within the organization. External sources may include market research reports, industry publications, customer feedback, expert opinions, and benchmarking studies.

Data Collection Methods: Depending on the nature of the decision and the information needed, various data collection methods may be employed. This could involve quantitative methods such as surveys, statistical analysis, and financial modeling, as well as qualitative methods such as interviews, focus groups, and case studies. Combining multiple data collection methods can provide a more comprehensive understanding of the decision context.

Analysis of Information: Once the information is gathered, it needs to be analyzed to extract meaningful insights and identify patterns or trends. This may involve summarizing data, identifying key findings, conducting comparative analysis, and synthesizing information from multiple sources. Data analysis tools and techniques can help streamline this process and identify relevant insights more efficiently.

Validation and Verification: It’s essential to ensure the accuracy, reliability, and relevance of the information gathered. Decision makers should verify the credibility of sources, cross-check data from multiple sources, and validate findings through independent verification or peer review where possible. This helps minimize the risk of relying on inaccurate or biased information in the decision-making process.

Continuous Learning: Gathering information is not a one-time activity but rather an ongoing process throughout the decision-making lifecycle. Decision makers should remain open to new information, update their understanding of the decision context as new data becomes available, and incorporate insights from ongoing monitoring and evaluation activities into their decision-making efforts.

Overall, gathering information provides decision makers with the knowledge and insights needed to make informed decisions that are based on a thorough understanding of the decision context and the factors that may influence outcomes. It sets the foundation for the subsequent steps in the decision-making process by providing the necessary information to evaluate alternative options and identify the best course of action.

2.4 Generating Alternatives

Generating Alternatives is a pivotal step in the decision-making process where individuals or teams brainstorm and develop a range of possible solutions or courses of action to address the decision criteria established earlier. This step is critical for fostering creativity, exploring diverse perspectives, and expanding the pool of options available for consideration. Here’s a closer look at the key aspects of generating alternatives:

Brainstorming: The process typically begins with a brainstorming session where decision makers generate ideas freely and without judgment. This encourages creativity and allows participants to explore unconventional or out-of-the-box solutions. Brainstorming sessions may involve individual ideation followed by group discussion, or collaborative brainstorming where ideas are generated collectively.

Diverse Perspectives: It’s essential to involve individuals with diverse backgrounds, expertise, and perspectives in the process of generating alternatives. This diversity can bring fresh insights, innovative ideas, and different approaches to problem-solving. Encouraging participation from stakeholders representing various departments, disciplines, or levels within the organization can lead to a broader set of alternatives.

Consideration of Constraints: While brainstorming alternatives, decision makers should consider any constraints or limitations that may impact the feasibility or viability of proposed solutions. These constraints may include budgetary restrictions, time constraints, resource limitations, regulatory requirements, technological constraints, or other practical considerations. Identifying constraints upfront helps narrow down the list of alternatives to those that are realistically achievable.

Creativity Techniques: Various creativity techniques and tools can be employed to stimulate idea generation and facilitate the exploration of alternative solutions. These techniques may include mind mapping, role-playing, analogical thinking, reverse brainstorming, lateral thinking, or the use of creative prompts or stimuli. Creativity exercises can help unlock innovative ideas and break through cognitive barriers that may limit conventional thinking.

Evaluation of Alternatives: As alternatives are generated, they should be documented and organized for further evaluation in the subsequent step of the decision-making process. Each alternative should be described clearly, outlining its key features, potential benefits, drawbacks, and implications. Decision makers can use this information to assess the feasibility, effectiveness, risks, and potential outcomes of each alternative in relation to the decision criteria established earlier.

Overall, generating alternatives is a dynamic and creative process that expands the range of options available for consideration in the decision-making process. By fostering creativity, encouraging diverse perspectives, and considering practical constraints, decision makers can develop innovative solutions that address the underlying problem or opportunity effectively. Generating a robust set of alternatives lays the groundwork for thorough evaluation and selection of the best course of action in the subsequent steps of the decision-making process.

2.5 Analyzing Alternatives

Analyzing Alternatives is a crucial step in the decision-making process where decision makers systematically evaluate each alternative against the established decision criteria. This step involves assessing the feasibility, effectiveness, risks, and potential outcomes of each alternative to determine which option best aligns with the organization’s objectives and constraints. Here’s a detailed explanation of the key aspects of analyzing alternatives:

Feasibility Assessment: Decision makers assess the practicality and achievability of each alternative by considering factors such as available resources, time constraints, technical feasibility, and organizational capabilities. They evaluate whether each option can be implemented within the specified constraints and whether the necessary resources and expertise are readily available.

Effectiveness Evaluation: Each alternative is evaluated based on its ability to address the underlying problem or opportunity effectively. Decision makers consider the extent to which each option aligns with the desired outcomes and contributes to achieving the organization’s goals. They assess the potential impact of each alternative on key performance indicators and stakeholder satisfaction.

Risk Analysis: Decision makers identify and assess the risks associated with each alternative, including potential drawbacks, uncertainties, and adverse consequences. They consider factors such as financial risks, operational risks, legal risks, reputational risks, and strategic risks. Risk analysis helps decision makers anticipate and mitigate potential challenges and uncertainties that may arise during implementation.

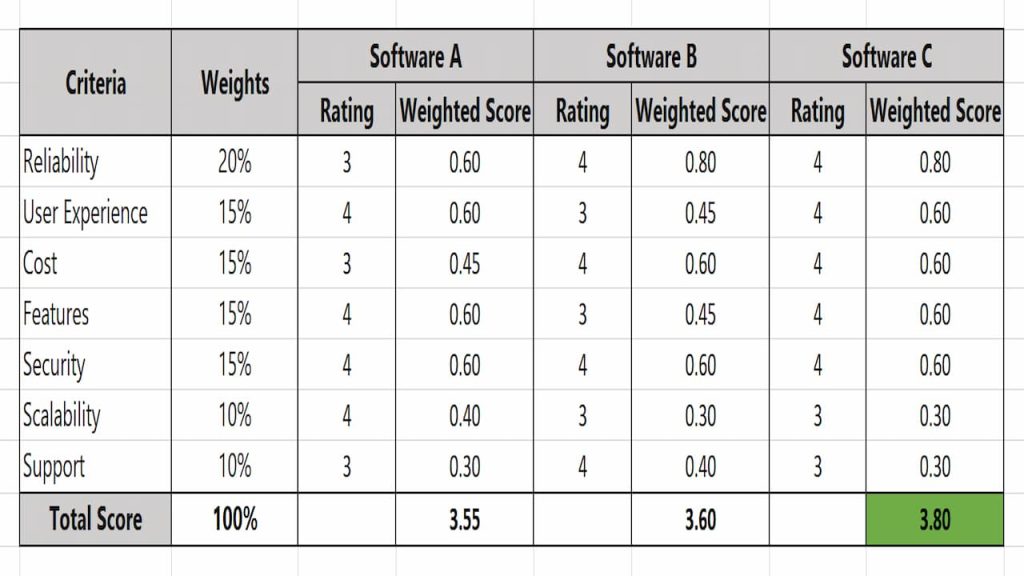

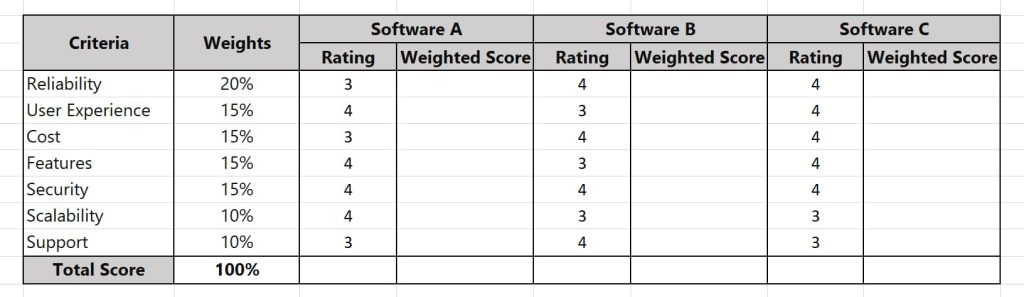

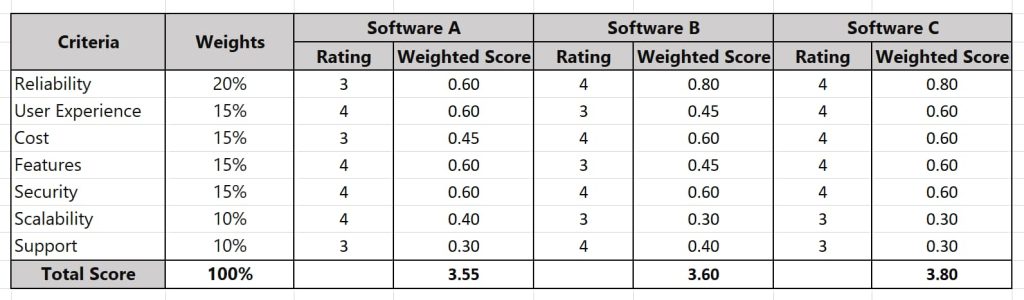

Outcome Prediction: Decision makers use tools and techniques such as cost-benefit analysis, SWOT analysis, decision matrices, scenario analysis, or simulation models to predict the potential outcomes of each alternative. They quantify the expected benefits, costs, and trade-offs associated with each option and weigh these factors against the decision criteria established earlier. Outcome prediction provides decision makers with valuable insights into the potential implications of their choices and helps guide their decision-making process.

Comparative Evaluation: Decision makers compare and contrast the strengths and weaknesses of each alternative to identify their relative advantages and disadvantages. They consider trade-offs between competing priorities, such as short-term gains versus long-term benefits, cost savings versus quality, or risk mitigation versus innovation. Comparative evaluation enables decision makers to make informed trade-offs and select the alternative that offers the most favorable balance of benefits and risks.

Overall, analyzing alternatives involves a systematic and rigorous evaluation of the available options to identify the most promising course of action. By considering feasibility, effectiveness, risks, potential outcomes, and comparative merits, decision makers can make informed decisions that maximize value and contribute to organizational success. Analyzing alternatives is a critical step that bridges the gap between idea generation and decision implementation, ensuring that decisions are based on thorough analysis and strategic consideration of all relevant factors.

2.6 Making the Decision

Making the Decision is a pivotal step in the decision-making process where decision makers choose the best alternative among the options generated and analyzed in the previous steps. This step involves synthesizing the information gathered, weighing the pros and cons of each alternative, considering trade-offs, and ultimately making a choice that aligns with the established decision criteria and objectives. Here’s a deeper dive into the key aspects of making the decision:

Synthesizing Information: Decision makers synthesize the information gathered during the gathering and analysis phases to gain a comprehensive understanding of each alternative’s strengths, weaknesses, risks, and potential outcomes. They review the findings from the analysis of alternatives and consider how each option aligns with the established decision criteria and objectives.

Weighing Pros and Cons: Decision makers weigh the advantages and disadvantages of each alternative, considering factors such as feasibility, effectiveness, risks, costs, benefits, and strategic implications. They evaluate the potential impact of each option on the organization’s goals, stakeholders, resources, and long-term sustainability. Weighing the pros and cons helps decision makers make informed trade-offs and prioritize competing priorities.

Considering Trade-Offs: Decision making often involves trade-offs between competing objectives, constraints, and stakeholders’ interests. Decision makers consider the trade-offs associated with each alternative, such as short-term gains versus long-term benefits, cost savings versus quality, or risk mitigation versus innovation. They balance competing priorities and seek to identify the option that offers the most favorable balance of benefits and risks.

Balancing Competing Priorities: Decision makers balance competing priorities and considerations when making the final decision. They take into account various factors, such as financial implications, organizational capabilities, market dynamics, regulatory requirements, and ethical considerations. Balancing competing priorities ensures that the chosen alternative aligns with the organization’s overall strategy and values.

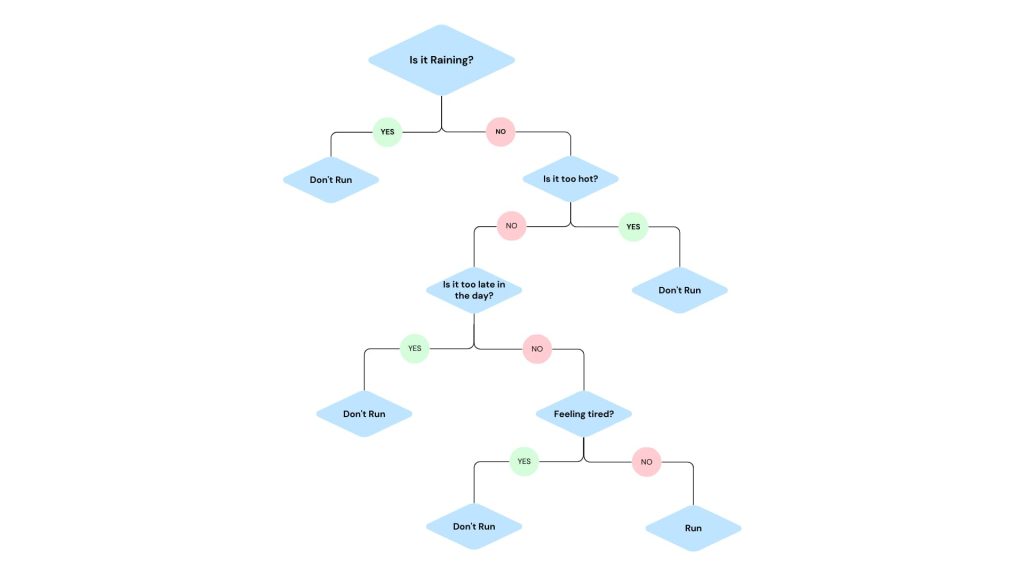

Decision Making Process: Decision makers follow a systematic decision-making process, which may involve consensus building, consultation with stakeholders, or seeking input from subject matter experts. They use decision-making tools and techniques, such as decision matrices, decision trees, or multi-criteria decision analysis, to facilitate the decision-making process and enhance the quality of the decision. The decision-making process ensures that decisions are made in a transparent, objective, and accountable manner.

Overall, making the decision is a critical step in the decision-making process that requires careful consideration, analysis, and judgment. By synthesizing information, weighing pros and cons, considering trade-offs, balancing competing priorities, and following a systematic decision-making process, decision makers can choose the best alternative that maximizes value and contributes to organizational success. Making effective decisions is essential for achieving strategic objectives, managing risks, and driving performance improvement in organizations.

2.7 Implementing the Decision

Implementing the Decision is the stage in the decision-making process where the chosen alternative is put into action. It involves translating the decision into practical steps, allocating resources, assigning responsibilities, and initiating the necessary actions to execute the decision effectively. Here’s a closer look at the key components of implementing the decision:

Developing an Implementation Plan: Before taking action, decision makers develop a detailed implementation plan that outlines the steps, tasks, timelines, and resources required to execute the decision. The implementation plan serves as a roadmap for translating the decision into tangible outcomes and ensures that everyone involved understands their roles and responsibilities.

Allocating Resources: Decision makers allocate the necessary resources, including financial, human, technological, and material resources, to support the implementation of the decision. This may involve securing funding, allocating budgets, reallocating personnel, procuring equipment or supplies, and mobilizing other resources needed to execute the decision effectively.

Assigning Responsibilities: Decision makers assign specific responsibilities and tasks to individuals or teams responsible for implementing the decision. Clear roles and responsibilities are defined to ensure accountability, coordination, and alignment among stakeholders. Assigning responsibilities helps streamline the implementation process and ensures that tasks are completed in a timely and efficient manner.

Initiating Action: With the implementation plan in place and resources allocated, decision makers initiate the necessary actions to execute the decision. This may involve launching new initiatives, implementing new processes or procedures, introducing changes to existing systems or structures, or pursuing other activities aimed at achieving the desired outcomes of the decision.

Overall, implementing the decision is a critical phase in the decision-making process that requires careful planning, coordination, and execution. By developing a clear implementation plan, allocating resources effectively, assigning responsibilities and initiating action, decision makers can ensure that the chosen alternative is successfully translated into action and achieves the desired outcomes. Effective implementation is essential for realizing the benefits of the decision and driving organizational success.

2.8 Monitoring and Evaluation

Monitoring and Evaluation is a crucial step in the decision-making process where decision makers assess the progress and outcomes of the implemented decision against the established criteria. Here’s a detailed explanation of this step:

Continuous Monitoring: Decision makers continuously monitor the implementation of the decision to track progress and ensure that activities are proceeding according to plan. Monitoring involves collecting data, observing performance indicators, and staying informed about the status of the decision implementation process. This ongoing oversight allows decision makers to identify any deviations, delays, or challenges early on and take corrective action as needed.

Tracking Progress: Decision makers track key performance indicators (KPIs), milestones, and deliverables to measure progress against the established benchmarks and timelines. By comparing actual results with the targets set in the implementation plan, decision makers can assess whether the decision implementation is on track and achieving the desired outcomes. Tracking progress provides insights into the effectiveness of the implemented measures and helps identify areas of success or improvement.

Evaluating Outcomes: Decision makers evaluate the outcomes of the decision implementation against the predefined criteria and objectives. This evaluation involves assessing the extent to which the implemented measures have achieved the desired results, addressed the underlying problem or challenge, and contributed to organizational goals. Decision makers analyze the qualitative and quantitative outcomes, considering factors such as efficiency, effectiveness, quality, and stakeholder satisfaction.

Gathering Feedback: Decision makers gather feedback from stakeholders, including employees, customers, partners, and other relevant parties, to assess their perceptions and experiences with the implemented decision. Feedback may be collected through surveys, interviews, focus groups, or other feedback mechanisms. By soliciting input from stakeholders, decision makers gain valuable insights into the impact of the decision implementation on various stakeholders and can identify areas for improvement.

Assessing Performance: Decision makers assess the performance of the decision implementation efforts based on the collected data, feedback, and evaluation findings. They analyze the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats associated with the implemented measures, identifying areas of success and areas that require attention or improvement. Assessing performance helps decision makers understand what worked well, what did not, and what lessons can be learned for future decision-making efforts.

Making Adjustments: Based on the monitoring and evaluation findings, decision makers make adjustments to the implementation plan, strategies, or tactics as needed to improve performance and achieve better outcomes. This may involve revising timelines, reallocating resources, modifying strategies, or implementing corrective measures to address any issues or challenges identified during the evaluation process. Making adjustments ensures that the decision implementation remains responsive to changing circumstances and stakeholder needs.

Overall, monitoring and evaluation play a critical role in the decision-making process by providing decision makers with valuable feedback, insights, and data to assess the effectiveness of the implemented decision, identify areas for improvement, and drive continuous learning and adaptation. By systematically monitoring progress, evaluating outcomes, gathering feedback, assessing performance, and making adjustments as needed, decision makers can enhance the success and impact of their decisions over time.

2.9 Learning and Adaptation

Learning and Adaptation is the final step in the decision-making process, focusing on reflection, knowledge acquisition, and improvement for future decision-making efforts. Here’s a detailed explanation of this step:

Reflecting on the Decision-making Process: Decision makers engage in reflection to review and analyze the entire decision-making process, from identifying the need for a decision to implementing and evaluating the chosen alternative. They consider the effectiveness of each step, identify strengths and weaknesses, and reflect on the challenges encountered along the way. Reflecting on the decision-making process provides insights into what worked well, what could have been done differently, and what lessons can be learned for future decisions.

Identifying Lessons Learned: Decision makers identify key lessons learned from the decision-making experience, drawing on both successes and failures. They reflect on the outcomes of the decision, the effectiveness of the chosen alternative, and the impact on stakeholders. By identifying lessons learned, decision makers gain valuable insights into what contributed to the success or failure of the decision, what factors influenced the outcomes, and what strategies were most effective in addressing the problem or opportunity at hand.

Incorporating Insights into Future Decision-making Efforts: Decision makers incorporate the insights gained from reflection and lessons learned into future decision-making efforts. They update their knowledge base, decision-making frameworks, and approaches based on the experiences and feedback gathered during the decision-making process. This may involve revising decision criteria, refining analytical techniques, adopting new tools or methodologies, or enhancing collaboration and communication practices. By incorporating insights into future decision-making efforts, decision makers improve their decision-making capabilities and increase the likelihood of achieving better outcomes over time.

Driving Continuous Improvement: Learning and adaptation drive continuous improvement in decision-making processes and outcomes. Decision makers embrace a culture of learning, where they continuously seek to enhance their skills, knowledge, and decision-making practices. They encourage feedback, collaboration, and experimentation, fostering an environment where individuals are empowered to innovate, learn from mistakes, and strive for excellence in decision making. By promoting continuous improvement, decision makers cultivate a dynamic and adaptive organizational culture that is resilient, agile, and capable of responding effectively to changing circumstances and emerging challenges.

Overall, learning and adaptation are essential components of the decision-making process, enabling decision makers to evolve, grow, and enhance their decision-making capabilities over time. By reflecting on past experiences, identifying lessons learned, and incorporating insights into future decision-making efforts, decision makers can drive continuous improvement, foster innovation, and achieve greater success in addressing complex problems, seizing opportunities, and achieving organizational goals.

2.10 Example Scenario

Scenario: James is the manager of a small retail store that sells a variety of products, including clothing, accessories, and home goods. Recently, James noticed a decline in sales and customer satisfaction levels, indicating that there may be underlying issues affecting the store’s performance. Concerned about the situation, James decides to utilize the decision-making process to address these challenges and improve the store’s overall performance.

Identifying the Need for a Decision: James recognizes the need for a decision when he notices a decline in sales and customer satisfaction levels. He realizes that there may be underlying problems affecting the store’s performance that require attention.

Defining the Decision Criteria: James establishes the decision criteria, including increasing sales revenue, improving customer satisfaction ratings, and enhancing operational efficiency. These criteria serve as benchmarks for evaluating alternative solutions to address the store’s challenges.

Gathering Information: James begins by collecting relevant data and insights related to the store’s performance. He analyzes sales reports, customer feedback, employee observations, and market trends to gain a comprehensive understanding of the situation.

Generating Alternatives: Based on the gathered information, James brainstorms various alternatives to improve the store’s performance. These alternatives may include implementing promotional campaigns, optimizing the product mix, enhancing customer service training, or redesigning the store layout.

Analyzing Alternatives: James evaluates each alternative against the decision criteria to assess its feasibility, effectiveness, and potential outcomes. He conducts a cost-benefit analysis, considers potential risks, and weighs the pros and cons of each option.

Making the Decision: After careful analysis, James selects the best alternative based on the criteria established earlier. He decides to implement a combination of strategies, including launching a targeted marketing campaign, introducing new product lines based on customer preferences, and providing additional training for store staff to improve customer service.

Implementing the Decision: James develops a detailed implementation plan outlining the steps, timelines, and resources required to execute the chosen strategies. He allocates resources, assigns responsibilities to staff members, and initiates the necessary actions to implement the decision effectively.

Monitoring and Evaluation: Throughout the implementation phase, James closely monitors the progress of the initiatives and tracks key performance indicators such as sales revenue, customer satisfaction ratings, and operational efficiency. He gathers feedback from customers and employees, assesses performance against the established criteria, and makes adjustments as needed to ensure the success of the strategies.

Learning and Adaptation: After the initiatives have been implemented, James reflects on the decision-making process and identifies lessons learned from the experience. He incorporates insights gained from the monitoring and evaluation process into future decision-making efforts, continuously striving to improve the store’s performance over time.

By following the decision-making process, James successfully addresses the challenges facing the retail store and achieves his goal of improving sales revenue, customer satisfaction, and operational efficiency.

Recognizing the Need for Problem Solving: The Human Resources department of a company notices a decline in employee engagement levels through decreased productivity and increased turnover rates.

Defining the Problem Clearly: The HR team conducts surveys and holds meetings to understand the specific areas where employees are disengaged, such as lack of recognition, poor work-life balance, and unclear career growth opportunities.

Understanding the Scope and Significance of the Problem: They realize that low employee engagement not only affects individual performance but also impacts overall company culture and morale, in addition to the profitability.

3. Types of Decision Making

Decisions can be categorized into several types based on various factors such as complexity, time sensitivity, and involvement of stakeholders. Understanding the different types of decision-making can help us approach various situations more effectively. In this section, we will explore the different types of decision-making, including strategic, tactical, operational, programmed, and non-programmed decisions. Each type has its own characteristics and is used in different contexts. By learning about these types, we can better recognize the most suitable approach for any given situation, enhancing our ability to make informed and effective choices.

3.1 Programmed Decision Making

A programmed decision is a routine choice that follows established procedures, rules, or guidelines. These decisions are repetitive in nature and are typically made in response to recurring situations or problems that can be anticipated. Programmed decisions are characterized by their predictability, consistency, and reliance on predetermined criteria for decision making. They are often automated through technology or predefined algorithms to streamline processes and reduce the need for human intervention, especially for routine and repetitive tasks.

Here are some examples of programmed decision-making:

- Reordering Inventory: A retail store automatically reorders stock when inventory levels fall below a predetermined threshold. The store has a set policy to reorder a specific quantity of each item to maintain optimal stock levels.

- Employee Scheduling: A restaurant manager uses a scheduling software program to create weekly work schedules for employees. The software follows rules based on employee availability, required shifts, and labor laws to generate the schedule.

- Expense Approvals: A company’s finance department has a policy that expenses under a certain amount can be approved by department heads without further review. Any expense within this limit follows a standard approval process.

- Customer Service Responses: A call center representative uses a script to handle common customer inquiries. For frequently asked questions, the representative follows a set response to ensure consistency and efficiency in service.

- Loan Processing: A bank has criteria for approving small personal loans. When a customer’s application meets the specified criteria, the loan is automatically approved without further review by a loan officer.

- Maintenance Schedules: A manufacturing plant follows a scheduled maintenance routine for its machinery. The maintenance team performs checks and repairs based on a fixed schedule to prevent equipment breakdowns.

- Attendance Tracking: An educational institution uses an automated system to track student attendance. The system sends alerts to parents if a student misses a certain number of classes, based on predefined rules.

- Billing Processes: A utility company generates monthly bills for customers using an automated system. The system calculates charges based on usage data and applies standard rates and fees to produce accurate bills.

These examples illustrate how programmed decision-making relies on established rules and procedures to handle routine tasks efficiently, ensuring consistency and freeing up resources for more complex, non-programmed decisions.

Steps of Programmed Decision Making

The steps of programmed decision making typically involve the following:

Identification of the Situation: The first step in programmed decision making is to identify the situation or problem that requires a decision. This involves recognizing routine tasks or recurring issues that can be addressed using established procedures or rules.

Definition of Decision Criteria: Once the situation is identified, the decision criteria are defined. These criteria outline the specific factors or conditions that will be used to evaluate options and make a decision. Decision criteria are often based on organizational policies, best practices, or predetermined guidelines.

Collection of Relevant Information: In this step, relevant information related to the decision is collected and analyzed. This may involve gathering data, reviewing past experiences, or consulting relevant stakeholders to ensure that all pertinent information is considered.

Application of Decision Rules: With the decision criteria and information in hand, decision rules or procedures are applied to determine the appropriate course of action. These decision rules are predefined and outline the steps or actions to be taken based on specific conditions or circumstances.

Evaluation of Alternatives: Once the decision rules are applied, potential alternatives are evaluated against the established criteria to identify the most suitable option. This evaluation may involve comparing the pros and cons of each alternative and assessing their potential impact on the desired outcomes.

Selection of the Best Alternative: Based on the evaluation of alternatives, the best option is selected as the course of action to be taken. This decision is made in accordance with the predefined decision rules and criteria, ensuring consistency and alignment with organizational objectives.

Implementation of the Decision: After the best alternative is selected, the decision is implemented by taking the necessary actions to execute the chosen course of action. This may involve assigning tasks, allocating resources, and communicating decisions to relevant stakeholders.

Monitoring and Feedback: The final step in programmed decision making involves monitoring the implementation of the decision and gathering feedback on its effectiveness. This feedback helps identify any deviations from the expected outcomes and provides insights for future decision making.

By following these steps, organizations can effectively navigate routine tasks and recurring issues using programmed decision making, ensuring consistency, efficiency, and alignment with organizational goals.

Characteristics of Programmed Decision

The characteristics of programmed decisions include:

Repetitive Nature: Programmed decisions are made repeatedly in response to similar situations or problems. They become routine as they occur frequently and follow a consistent pattern.

Established Procedures: Programmed decisions are based on established procedures, rules, or guidelines that dictate the appropriate course of action in specific situations. These procedures are developed in advance to provide a structured framework for decision making.

Predictability: Due to their repetitive nature and reliance on established procedures, programmed decisions are predictable and can be anticipated in advance. This predictability allows for efficient planning and resource allocation.

Automation: Programmed decisions are often automated through technology or predefined algorithms. This automation streamlines decision-making processes and reduces the need for human intervention, especially for routine and repetitive tasks.

Low-Level Management: Programmed decisions are typically made at the lower levels of management or by frontline employees responsible for executing day-to-day operations. They are routine and do not require strategic or complex analysis.

Efficiency and Consistency: Programmed decision making contributes to organizational efficiency and consistency by ensuring that routine tasks are handled consistently according to established procedures. This consistency helps maintain quality standards and facilitates smooth operations.

Reliance on Predefined Criteria: Programmed decisions rely on predefined criteria or rules for decision making. These criteria are developed based on past experience, best practices, or organizational policies to guide decision making in routine situations.

Understanding these characteristics helps organizations effectively utilize programmed decision making to address routine tasks and streamline operational processes.

Advantages of Programmed Decisions

The advantages of programmed decisions include:

Efficiency: Programmed decisions streamline decision-making processes by providing established procedures or rules for routine tasks. This efficiency saves time and resources, allowing organizations to focus on higher-priority activities.

Consistency: Programmed decisions ensure consistency in decision making by following predefined criteria or guidelines. This consistency helps maintain quality standards and ensures uniformity in outcomes across different situations or locations.

Predictability: Programmed decisions are predictable and can be anticipated in advance, allowing for effective planning and resource allocation. This predictability reduces uncertainty and facilitates smooth operations.

Reduced Error Rates: Programmed decisions minimize the risk of errors and mistakes by providing clear guidelines and procedures for decision making. This reduces the likelihood of human error and improves accuracy in task execution.

Automation: Programmed decisions can be automated through technology or predefined algorithms, further enhancing efficiency and reducing the need for manual intervention. Automation streamlines processes and eliminates repetitive tasks, freeing up time for more strategic activities.

Employee Empowerment: Programmed decisions empower employees by providing clear guidelines and procedures for task execution. This clarity helps employees understand their roles and responsibilities, leading to increased confidence and job satisfaction.

Scalability: Programmed decisions can be scaled across different situations or locations, allowing organizations to apply consistent standards and practices across the board. This scalability facilitates growth and expansion while maintaining operational efficiency.

Overall, programmed decisions offer numerous advantages that contribute to organizational effectiveness, efficiency, and consistency. By leveraging established procedures and guidelines, organizations can streamline decision making, minimize errors, and focus on strategic priorities for long-term success.

Limitations of Programmed Decisions

While programmed decisions offer several advantages, they also have limitations that organizations should be aware of:

Inflexibility: Programmed decisions rely on established procedures or rules, which can limit flexibility in response to changing circumstances or unexpected situations. This inflexibility may hinder the organization’s ability to adapt and innovate in dynamic environments.

Limited Applicability: Programmed decisions are suitable for routine tasks and recurring situations but may not be applicable to complex or novel problems that require creative thinking and adaptive responses. This limitation restricts the scope of programmed decision making to routine and repetitive tasks.

Lack of Adaptability: Programmed decisions are based on predefined criteria or guidelines, which may not always align with the unique characteristics of individual situations. This lack of adaptability can lead to suboptimal outcomes or missed opportunities for improvement.

Overreliance on Procedures: Programmed decision making can foster an overreliance on established procedures or rules, leading to complacency and a reluctance to deviate from the status quo. This overreliance may stifle innovation and impede organizational growth.

Resistance to Change: Programmed decisions may create resistance to change among employees who are accustomed to following established procedures. Introducing new processes or procedures may encounter resistance, as employees may perceive them as disruptive or unnecessary.

Potential for Errors: Despite providing clear guidelines and procedures, programmed decisions are still susceptible to errors and mistakes, particularly if the underlying criteria or rules are flawed or outdated. This potential for errors can undermine the effectiveness of programmed decision making.

Limited Strategic Value: Programmed decisions are primarily focused on routine tasks and operational efficiency, which may limit their strategic value in driving long-term organizational success. Strategic decisions often require more holistic and forward-thinking approaches that go beyond predefined procedures.

Difficulty in Handling Exceptions: Programmed decisions may struggle to handle exceptions or unusual situations that fall outside the scope of established procedures. This difficulty in handling exceptions can lead to delays, inefficiencies, or suboptimal outcomes.

Despite these limitations, programmed decision making remains an important tool for streamlining routine tasks and maintaining consistency in organizational operations. However, organizations should also recognize the need for flexibility and adaptability to address the complexities of modern business environments effectively.

Applications of Programmed Decision Making

Reordering Inventory: In retail and manufacturing settings, programmed decisions are often used to determine when to reorder inventory. Organizations establish predefined criteria, such as reorder points and order quantities, based on factors like demand forecasts, lead times, and inventory turnover rates. When stock levels fall below a certain threshold, an automated process triggers the reorder decision, ensuring that inventory is replenished in a timely manner.

Employee Scheduling: Many organizations use programmed decision making to create employee schedules. Managers follow set schedule templates and predefined criteria, such as employee availability, skill levels, and labor regulations, to assign shifts and allocate work hours. This helps ensure that staffing levels meet operational requirements while adhering to labor laws and employee preferences.

Budget Allocation: Programmed decisions are commonly used in budgeting processes to allocate funds for routine expenses and activities. Organizations establish predefined budgetary guidelines and allocation criteria based on factors such as historical spending patterns, departmental priorities, and financial objectives. When preparing budgets, managers follow these guidelines to allocate resources across different cost centers or budget categories.

Customer Service Routing: In customer service operations, programmed decision making is employed to route customer inquiries to the appropriate departments or agents. Organizations establish predefined criteria, such as customer demographics, inquiry types, and agent availability, to determine how incoming requests are directed. Automated systems use these criteria to route inquiries efficiently, ensuring that customers receive prompt and accurate assistance.

Compliance Monitoring: Programmed decisions are utilized in compliance monitoring processes to ensure adherence to regulatory requirements and organizational policies. Organizations establish predefined compliance criteria and monitoring procedures based on legal obligations, industry standards, and internal guidelines. Automated systems are often employed to track compliance metrics, generate reports, and flag instances of non-compliance for further investigation.

Overall, programmed decision making is applied in diverse organizational functions and processes to streamline operations, enhance productivity, and ensure consistency in decision making. By automating routine tasks and standardizing procedures, organizations can focus on strategic priorities and achieve their goals more effectively.

Example Scenario for Programmed Decision Making

Scenario: Inventory Replenishment in a Retail Store

In a retail store, programmed decision making is utilized to manage inventory levels and ensure that products are consistently available to meet customer demand. Let’s explore how programmed decision making is applied in this scenario:

Background: ABC Retail is a popular clothing store that offers a wide range of apparel for men, women, and children. The store operates multiple locations and experiences fluctuating demand for different products throughout the year.

Identification of the Situation: The inventory manager at ABC Retail regularly monitors stock levels to identify when inventory needs to be replenished. Using sales data, historical trends, and forecasts, the inventory manager identifies products that are running low or approaching reordering thresholds.

Definition of Decision Criteria: Predefined criteria are established to determine when inventory needs to be replenished. These criteria include reorder points, safety stock levels, lead times, and order quantities. For example, if the inventory of a particular item falls below the reorder point, a decision is triggered to initiate the replenishment process.

Collection of Relevant Information: The inventory manager collects relevant information, such as current inventory levels, sales data, supplier lead times, and stock reorder points, to inform the decision-making process. This information is regularly updated and maintained in the inventory management system.

Application of Decision Rules: Based on the predefined criteria and information collected, decision rules are applied to determine when and how much inventory to reorder. For instance, if the inventory of a product falls below the predetermined reorder point, an automated system generates a reorder request to the supplier.

Evaluation of Alternatives: The inventory manager evaluates different alternatives, such as ordering from different suppliers, adjusting order quantities, or expediting shipments, to determine the most cost-effective and efficient approach for replenishing inventory.

Selection of the Best Alternative: After evaluating alternatives, the inventory manager selects the best option for replenishing inventory based on factors such as cost, lead time, and supplier reliability. The decision is made in accordance with the predefined decision criteria and rules established by the organization.

Implementation of the Decision: Once the decision is made, the inventory manager initiates the replenishment process by placing orders with the selected suppliers. Automated systems generate purchase orders, track order status, and coordinate deliveries to ensure that inventory is replenished in a timely manner.

Monitoring and Feedback: The inventory manager monitors the implementation of the decision and gathers feedback on inventory levels, stock replenishment, and supplier performance. Any deviations from the expected outcomes are addressed promptly, and adjustments are made to improve the effectiveness of the inventory replenishment process.

Through programmed decision making, ABC Retail can effectively manage inventory levels, optimize stock replenishment processes, and ensure that products are consistently available to meet customer demand. This streamlined approach to inventory management helps ABC Retail maintain operational efficiency, minimize stockouts, and enhance customer satisfaction.

3.2 Non-Programmed Decision Making

A non-programmed decision is a unique or novel choice that arises in response to unfamiliar or unanticipated situations, problems, or opportunities. Unlike programmed decisions, which are routine and follow established procedures or rules, non-programmed decisions are complex, unstructured, and require careful analysis, evaluation, and judgment. Non-programmed decisions typically involve higher levels of uncertainty, ambiguity, and risk, as they often lack clear guidelines or predefined criteria for decision making.

Here are some examples of non-programmed decision-making:

- Business Expansion: A company decides to enter a new market or open a new branch. This decision involves analyzing market conditions, assessing risks, and developing a strategic plan, as there are no standard procedures for such complex decisions.

- Product Development: A tech company decides to develop and launch a new product. This requires innovative thinking, market research, and cross-functional collaboration to create something new that meets customer needs and stands out in the market.

- Crisis Management: A company faces a sudden public relations crisis due to a product recall. The management team must quickly decide how to handle the situation, communicate with stakeholders, and restore the company’s reputation, often without a clear, predefined strategy.

- Mergers and Acquisitions: A corporation considers merging with or acquiring another company. This involves detailed financial analysis, cultural assessments, and strategic planning, as each merger or acquisition is unique and complex.

- Legal Disputes: A company faces a significant legal issue or lawsuit. Deciding on the legal strategy, whether to settle or fight in court, and managing the implications of the decision are complex tasks that do not follow a set formula.

- Policy Changes: A government body decides to implement a new policy or change existing regulations. This involves analyzing societal needs, potential impacts, stakeholder opinions, and long-term consequences, making it a non-routine decision.

- Cultural Change Initiatives: An organization decides to overhaul its corporate culture to improve employee satisfaction and performance. This requires diagnosing current cultural issues, envisioning desired changes, and implementing strategies to shift behaviors and mindsets.

- Entering a Strategic Partnership: A business considers forming a partnership or alliance with another company to enhance capabilities or market reach. This decision involves assessing strategic fit, negotiating terms, and planning integration, which are all unique to the specific situation.

These examples demonstrate how non-programmed decision-making addresses situations that are novel, complex, and critical, requiring customized solutions and strategic thinking to navigate effectively.

Non-programmed decisions require careful consideration, critical thinking, and adaptive responses to navigate complex and uncertain situations effectively. While programmed decisions are suitable for routine tasks and predictable situations, non-programmed decisions are essential for addressing novel challenges, driving innovation, and shaping the strategic direction of organizations.

Steps of Non-Programmed Decision Making

The steps involved in non-programmed decision making typically include:

Identification of the Problem or Opportunity: The first step in non-programmed decision making is to identify the problem or opportunity that requires a decision. This may involve recognizing an emerging issue, a new challenge, or an opportunity for improvement or innovation.

Gathering Information: Once the problem or opportunity is identified, relevant information is gathered to better understand the situation, its underlying causes, and potential implications. This may involve collecting data, conducting research, seeking input from stakeholders, and analyzing external factors that may impact the decision.

Generating Alternatives: In this step, a range of alternative options or courses of action is generated to address the problem or capitalize on the opportunity. Decision makers brainstorm creative solutions, explore different approaches, and consider various perspectives to generate a comprehensive list of alternatives.

Evaluating Alternatives: Each alternative is carefully evaluated based on predefined criteria, such as feasibility, effectiveness, potential risks, and alignment with organizational goals and values. Decision makers assess the strengths and weaknesses of each option, weigh the potential outcomes, and consider the trade-offs involved.

Making the Decision: After evaluating the alternatives, a decision is made based on the analysis and judgment of decision makers. The selected option is deemed to be the most appropriate course of action given the information available, the decision criteria, and the organization’s objectives.

Implementing the Decision: Once the decision is made, it is put into action through implementation. This may involve developing a detailed plan, allocating resources, assigning responsibilities, and communicating the decision to relevant stakeholders. Effective implementation is critical to ensure that the chosen course of action is executed successfully.

Monitoring and Adjusting: The final step in non-programmed decision making is to monitor the implementation of the decision and gather feedback on its effectiveness. Decision makers track the progress, assess the outcomes, and make adjustments as needed to address any unforeseen challenges or changes in circumstances. This iterative process allows for continuous improvement and adaptation over time.

By following these steps, organizations can navigate complex and uncertain situations effectively, make informed decisions, and achieve their strategic objectives. Non-programmed decision making requires critical thinking, creativity, and adaptability to address novel challenges and capitalize on emerging opportunities.

Characteristics of Non-Programmed Decision

The characteristics of non-programmed decisions include:

Uniqueness: Non-programmed decisions are unique and specific to the situation at hand. Unlike programmed decisions, which follow established procedures or rules, non-programmed decisions arise in response to unfamiliar or unanticipated situations that require innovative thinking and creative problem-solving.

Complexity: Non-programmed decisions are often complex and multifaceted, involving multiple factors, stakeholders, and potential outcomes. These decisions may lack clear guidelines or predefined criteria for decision making, requiring careful analysis, evaluation, and judgment.

Uncertainty: Non-programmed decisions are associated with higher levels of uncertainty and ambiguity compared to programmed decisions. Decision makers may lack complete information or face conflicting data, making it challenging to assess the potential risks and benefits of different options.

Strategic Importance: Non-programmed decisions are strategically significant and can have a significant impact on the organization’s future direction, success, and competitive position. These decisions may involve setting long-term goals, entering new markets, developing innovative products or services, or responding to external threats and opportunities.

Judgment and Expertise: Non-programmed decisions rely heavily on the judgment, expertise, and experience of decision makers. Given the complexity and uncertainty involved, decision makers must carefully evaluate the available information, weigh the potential consequences of different choices, and make informed judgments based on their insights and analysis.

Adaptability: Non-programmed decisions require adaptability and flexibility to respond effectively to changing circumstances or unexpected developments. Decision makers must be willing to adjust their strategies, reconsider their assumptions, and explore new approaches as the situation evolves.

Decision Maker’s Discretion: Non-programmed decisions often grant decision makers a high degree of discretion and autonomy in determining the best course of action. Unlike programmed decisions, which follow predefined procedures or rules, non-programmed decisions allow decision makers to exercise their judgment and creativity in addressing unique challenges and opportunities.

Long-term Impact: Non-programmed decisions typically have long-term implications and consequences for the organization. These decisions may shape the organization’s future direction, influence its competitive position, and impact its relationships with stakeholders. As such, decision makers must carefully consider the potential long-term effects of their decisions and plan accordingly.

By understanding these characteristics, organizations can effectively navigate non-programmed decision making, address complex challenges, and capitalize on emerging opportunities to achieve their strategic objectives.

Advantages of Non-Programmed Decisions

The advantages of non-programmed decision making include:

Adaptability: Non-programmed decisions allow organizations to adapt and respond flexibly to unique or novel situations. Unlike programmed decisions, which follow predetermined procedures, non-programmed decisions empower decision-makers to explore creative solutions and adapt their approaches based on changing circumstances.

Innovation: Non-programmed decisions encourage innovation and creativity by providing opportunities to explore new ideas and approaches. Decision-makers have the freedom to think outside the box and develop novel solutions to complex problems, driving organizational growth and competitive advantage.

Strategic Advantage: Non-programmed decisions can provide organizations with a strategic advantage by enabling them to capitalize on emerging opportunities or navigate unforeseen challenges more effectively. By making informed, strategic choices, organizations can position themselves for long-term success and differentiation in the marketplace.

Customization: Non-programmed decisions allow for greater customization and tailoring of solutions to meet specific needs or objectives. Decision-makers can take into account unique factors, preferences, and constraints when crafting solutions, leading to more effective outcomes and higher levels of stakeholder satisfaction.

Learning and Development: Non-programmed decisions provide valuable learning opportunities for organizations and their employees. By grappling with complex problems and making strategic choices, decision-makers can enhance their problem-solving skills, critical thinking abilities, and leadership capabilities, contributing to personal and professional growth.

Competitive Advantage: Non-programmed decisions can confer a competitive advantage by enabling organizations to differentiate themselves from competitors and innovate in their products, services, or business processes. By taking calculated risks and pursuing innovative strategies, organizations can position themselves as industry leaders and disruptors in their respective markets.

Enhanced Stakeholder Engagement: Non-programmed decisions often involve consultation and collaboration with stakeholders, fostering a sense of involvement, ownership, and commitment to the decision-making process. By engaging stakeholders in meaningful dialogue and soliciting their input, organizations can build stronger relationships and foster a culture of transparency and trust.

Overall, non-programmed decision making offers numerous advantages that can contribute to organizational agility, innovation, and competitiveness. By embracing uncertainty and complexity, organizations can harness the full potential of non-programmed decisions to drive growth, achieve strategic objectives, and create value for stakeholders.

Limitations of Non-Programmed Decisions

The limitations of non-programmed decision making include:

Time and Resource Intensive: Non-programmed decisions often require significant time and resources to gather information, analyze options, and make informed choices. The complexity and uncertainty associated with non-programmed decisions may prolong the decision-making process, leading to delays and resource allocation challenges.

Risk of Error: Non-programmed decisions are inherently more uncertain and complex than programmed decisions, increasing the risk of errors, misjudgments, and suboptimal outcomes. Decision-makers may face challenges in evaluating alternatives, predicting outcomes, and balancing competing priorities, leading to potential mistakes or oversights.

Subjectivity and Bias: Non-programmed decisions are influenced by subjective factors such as individual judgment, biases, and personal preferences. Decision-makers may be prone to cognitive biases, emotional influences, or groupthink, which can cloud their judgment and undermine the quality and objectivity of decision-making processes.

Lack of Precedent: Non-programmed decisions often lack clear precedents or established guidelines, making it challenging for decision-makers to draw upon past experiences or best practices. The absence of historical data or relevant benchmarks may increase uncertainty and hinder decision-making effectiveness.

Resistance to Change: Non-programmed decisions may encounter resistance from stakeholders who are accustomed to established routines or traditional approaches. Introducing innovative solutions or pursuing unconventional strategies may face skepticism or opposition, hindering organizational change and innovation efforts.

Complexity and Ambiguity: Non-programmed decisions are characterized by their complexity, ambiguity, and uncertainty, which can overwhelm decision-makers and complicate the decision-making process. The multiplicity of factors, conflicting objectives, and unpredictable outcomes may create confusion and indecision, leading to analysis paralysis or decision-making gridlock.

Implementation Challenges: Non-programmed decisions may face implementation challenges due to their complexity and novelty. Translating strategic decisions into actionable plans, allocating resources effectively, and overcoming organizational resistance may require careful planning, coordination, and communication to ensure successful implementation.

Lack of Control: Non-programmed decisions may involve factors beyond the organization’s control, such as external market conditions, regulatory changes, or geopolitical events. The unpredictability of external influences may limit the organization’s ability to anticipate and mitigate risks, increasing vulnerability to external shocks or disruptions.

Overall, while non-programmed decision making offers opportunities for innovation, adaptability, and strategic advantage, organizations must also navigate the inherent challenges and limitations associated with complex, uncertain, and novel decision-making contexts. By understanding these limitations and implementing strategies to mitigate them, organizations can enhance the effectiveness and resilience of their non-programmed decision-making processes.

Applications of Non-Programmed Decision Making

Non-programmed decision making finds applications across various domains and industries where unique or novel situations require innovative solutions and strategic thinking. Some common applications of non-programmed decision making include:

Strategic Planning: Non-programmed decision making is essential for strategic planning processes, where organizations set long-term goals, define their vision and mission, and identify strategic priorities. Decision-makers must assess market trends, competitive dynamics, and emerging opportunities to formulate strategic initiatives and allocate resources effectively.

New Product Development: Non-programmed decision making is crucial for developing new products or services that meet evolving customer needs and market demands. Decision-makers must identify market gaps, conduct market research, and assess technological trends to innovate and differentiate their offerings in competitive markets.

Crisis Management: Non-programmed decision making is essential for managing crisis situations such as natural disasters, security breaches, or reputational crises. Decision-makers must act swiftly and decisively to mitigate risks, ensure the safety of stakeholders, and protect the organization’s reputation and assets.

Organizational Change: Non-programmed decision making is integral to managing organizational change initiatives such as mergers, acquisitions, restructuring, or cultural transformations. Decision-makers must navigate complexity, uncertainty, and resistance to change to implement strategic changes and drive organizational growth and competitiveness.

Strategic Alliances and Partnerships: Non-programmed decision making is critical for forming strategic alliances, partnerships, or collaborations with external stakeholders such as suppliers, customers, or competitors. Decision-makers must assess potential synergies, risks, and benefits to establish mutually beneficial relationships that create value and drive innovation.

Crisis Response and Recovery: Non-programmed decision making is essential for responding to and recovering from crisis events such as pandemics, economic downturns, or geopolitical crises. Decision-makers must develop contingency plans, mobilize resources, and adapt their strategies to address immediate challenges and position the organization for recovery and resilience.

Market Entry and Expansion: Non-programmed decision making is crucial for entering new markets or expanding into new geographic regions. Decision-makers must conduct market research, assess regulatory requirements, and evaluate competitive dynamics to develop entry strategies and seize growth opportunities.

Innovation and R&D Investments: Non-programmed decision making is vital for allocating resources to innovation and research and development (R&D) initiatives. Decision-makers must prioritize investments, evaluate technology trends, and assess market potential to drive innovation, develop new capabilities, and sustain competitive advantage.

Overall, non-programmed decision making plays a critical role in addressing complex, uncertain, and novel challenges, driving innovation, and shaping the strategic direction of organizations in dynamic and competitive environments. By embracing creativity, flexibility, and strategic thinking, decision-makers can capitalize on emerging opportunities and navigate uncertainty to achieve their strategic objectives.

Example Scenario for Non-Programmed Decision Making

Scenario: Strategic Expansion into a New Market

Background: XYZ Corporation is a global technology company specializing in software development and digital solutions. With a strong presence in established markets, XYZ Corporation is exploring opportunities for strategic expansion into a new geographic region to capitalize on emerging market trends and growth opportunities.

Identification of the Opportunity: The executive leadership team at XYZ Corporation identifies an opportunity for strategic expansion into a new geographic market—Southeast Asia. Market research indicates significant growth potential in the region, driven by increasing demand for digital solutions, rising smartphone penetration, and favorable regulatory environments for technology companies.